Black-grass often grabs the weed control headlines but there are several other grass-weeds that cause problems for farmers across the country. Here we summarise the main management techniques for some of the most problematic weeds.

Author

| 10th June 2021Staying in control of grass-weeds

While many growers appear to be making encouraging progress in getting on top of black-grass and brome, Italian ryegrass problems are growing across the country, according to the latest in a 20-year series of national grassweed management studies. Noticeable increases in resistance have also been seen in the past four years, in particular.

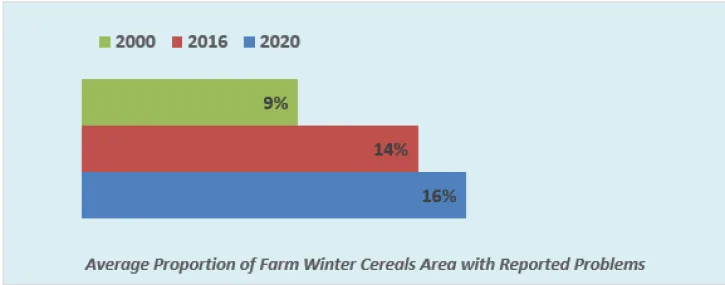

Back in 2000 when the first Roundup study was conducted, growers were encountering problems with Italian ryegrass across an average of 9% of their winter cereals area. This increased to 14% by 2016, with the independently-run 2020 survey of almost 200 farms growing over 22,000 ha of winter cereals showing a further rise to 16% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Changing Italian Ryegrass Problems

At the same time, the proportion of growers reporting increasing problems from the weed rose from 10% in 2000 to 16% in 2016 and 22% this year. And 21% are now experiencing serious or very serious resistant problems compared to 15% in 2016.

“Black-grass continues to be the main problem in every part of the country,” points out Bayer technical specialist, Thomas Scanlon. “On average, growers find it problematic across 33% of their winter cereals area, with 43% seeing increasing problems in recent years, and 55% reporting serious or very serious issues with resistance.

“Every area is, however, also reporting noticeably less of an increase in black-grass problems than four years ago, with more growers in the west and south of the country actually now seeing a decease than an increase. This suggests the integrated cultural controls being employed by many are bearing fruit.

“The picture is more mixed with brome,” he reports. “It’s currently a problem across an average of 15% of growers’ winter cereals area compared with 19% four years ago. However, there has been a noticeable increase in the average area affected in the east of England and East Midlands and a worrying rise in the overall proportion of farms reporting serious problems with resistance.

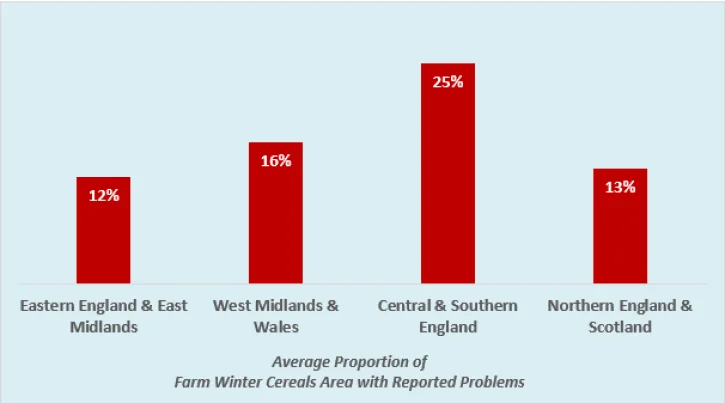

“Sadly, all the indicators are in the wrong direction with Italian ryegrass. Over 20% of growers in every region have been seeing an increase in problems with the weed in recent years, with those in central and southern England experiencing more widespread infestations than most.

(Figure 2). Reports of serious or very serious resistance have risen noticeably in many parts of the country too.

Figure 2: Regional Ryegrass Problems

“Unsurprisingly, black-grass continues to be markedly more widespread under minimum tillage than plough-based winter cereal establishment regimes, as does brome,” Tom notes. “This underlines the value of the rotational ploughing that continues to be a key cultural control technique for almost three quarters of growers.

“In contrast, Italian ryegrass appears to be equally problematic regardless of tillage system, suggesting that ploughing cannot necessarily be relied upon as such a valuable ‘reset’ here. So, maintaining a good balance of other cultural controls to support the available chemistry will be even more important.”

The importance of effective cultural controls is emphasised by the close relationship apparent in the Bayer study between the extent of Italian ryegrass problems and resistance. Only 18% of farms where the weed affects less than a tenth of the winter cereals area are currently experiencing serious or very serious problems with ryegrass resistance. But this rises to 47% where the weed is problematic across a quarter or more of the area.

While the majority of growers are clearly countering Italian ryegrass, alongside other grassweed threats, with the good stubble management, it is disappointing to see that 12% of those facing the greatest challenge from the weed are not using glyphosate ahead of either autumn-drilled cereals or spring cropping. This contrasts with just 4% of those with particular black-grass problems.

Equally, only 65% of those reporting ryegrass problems across a quarter or more of their winter cereals area are targeting the weed with an autumn pre-em and 18% with a peri-em herbicide against 90% and 31% respectively for those dealing with the same level of black-grass.

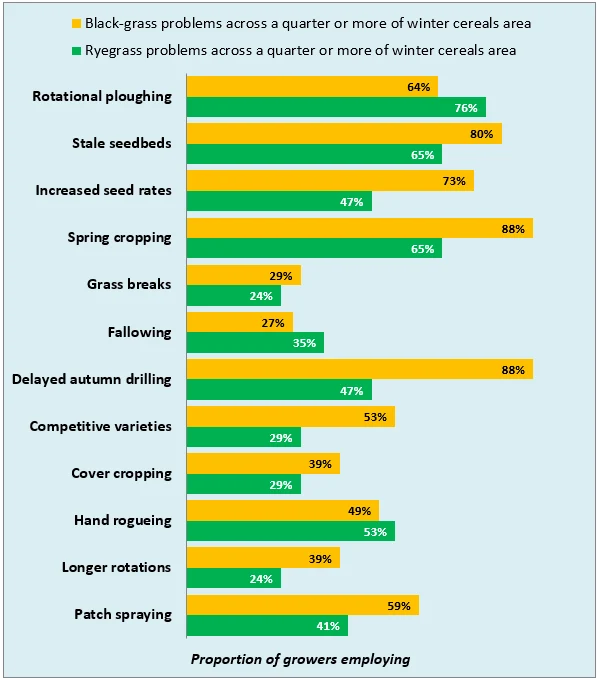

Worrying too are the differences the latest study reveals in the other cultural control practices being employed by those with similarly extensive Italian ryegrass and black-grass problems (Figure 3).

On average, those battling black-grass across a quarter or more of their winter cereals area are using 7.5 of the 12 main cultural techniques recognised as valuable compared to an average of 5.6 by those with comparable levels of ryegrass. What’s more, three quarters of these techniques are being employed less frequently – most of them very much so.

“The only widely-used technique receiving more attention in problem Italian ryegrass management is rotational ploughing,” observes Tom. “Yet ploughing is almost certainly less reliable in keeping a lid on this weed than it is with either black-grass or brome. This maybe because it is accompanied by less thorough stubble treatment, amongst other controls.

“The fact that less than half the growers with particular ryegrass problems are employing delayed autumn cereal drilling is especially concerning here. This is widely recognised to be as important in dealing with this weed as it is with black-grass.

“Also of clear value in managing Italian ryegrass but being employed far less widely than they are with black-grass – and really ought not to be – are stale seedbeds, higher cereal seed rates, longer rotations and patch-spraying.

Figure 3: Main Cultural Control Techniques

“Growers seem to be putting far less care and attention into managing Italian ryegrass than they do with black-grass,” he says. “This is a hugely false economy. If anything, indeed, they should be more concerned here. Ryegrass is around twice as competitive to cereals, can spread far more rapidly and is even more prone to resistance development than black-grass, courtesy of its particularly aggressive nature.

“With any gaps in grower defences acutely vulnerable to exploitation by the weed, effective control is vital before populations build to troublesome levels and continual management pressure is crucial.”

So, what does Tom Scanlon advise to keep Italian ryegrass firmly in check? Well, as problems can escalate so rapidly, he insists the key essential is a zero-tolerance policy.

In his experience, first class stubble hygiene must be the priority to take the pressure-off in-crop chemistry. This means cultivating immediately after combining, leaving the ground to green-up, spraying it off with the most active Roundup (glyphosate) formulation prior to drilling and then moving as little soil as possible during drilling to minimise early weed growth.

Like black-grass, he sees rotational ploughing as valuable. But only when several years of shallow tillage have kept the weed seed bank close to the soil surface. It also requires complete inversion or too much seed will escape burial to a depth from which it cannot emerge. And the ground should not be ploughed again for 4-5 years or viable seed can be brought back up into the germination zone.

Delaying wheat drilling until at least mid-October – and even later if there has been insufficient rain to stimulate weed germination – is the most crucial control alongside stubble hygiene in his view to give sufficient to eliminate as much of the autumn-germinating seed bank as possible ahead of drilling.

“I fully appreciate how difficult it is to hold your nerve for decent drilling conditions after last winter’s experience,” Tom accepts. “But a wheat crop full of Italian ryegrass really isn’t worth having, unless you plan to cut it for livestock feeding or AD. And the level of seed return will only make future problems worse.

“Later drilling can really help with pre-em activity too; providing, of course, you have a decent quality seedbed. So, it’s far better to have patience and, if necessary, sow into the New Year or switch to a spring crop if you can’t get the right conditions. Mauling the crop-in will always create more problems than it solves.”

Just like black-grass, the most effective residual chemistry is vital. Liberator’s combination of DFF and flufenacet continues to be the first choice pre-em, with the addition of Proclus (aclonifen) giving a useful 5-10% increase in ryegrass control. This new active for cereals is for strict pre-em only use.

For peri-emergence applications, the extra contact activity of metribuzin with flufenacet and DFF, in the form of Alternator or Octavian, is an advantage. And Atlantis (mesosulfuron + iodoulfuron) can still be valuable early post-em where resistance isn’t a problem. For spring use, it’s also worth considering Monolith (mesosulfuron + propoxycarbazone) for the best and broadest activity.

“Mixing a range of actives is very important as an anti-resistance strategy with Italian ryegrass,” notes Tom. “But stacking cultural controls is even more essential.

“Autumn drilling should always start with the lowest weed-risk fields. And where workloads mean higher risk fields need to be sown before mid-October go for a six-row barley or even rye instead. They are so much better at competing with the likes of Italian ryegrass than even the most competitive wheat varieties.

“Higher seed rates have also been shown to markedly improve crop competitiveness,” he adds. “And spraying-off badly-infested patches of crop in the early summer is always advisable to restrict seed return.

“As so many people now appreciate with black-grass, spring cropping can be immensely valuable in helping to break the Italian ryegrass cycle too – not least because it offers much more time for the best out-of-crop control with Roundup, even where cover cropping is employed.

“It’s important to appreciate that a single spring crop may not be sufficient where there are high levels of weed seed in the soil. Nor should spring cropping lead to a slackening-off in other key cultural controls – especially stubble management and delayed drilling.

“Keeping on top of Italian ryegrass in a far more determined and comprehensive way than many growers seem to be doing at the moment is the only can we ensure this grassweed doesn’t become at least as devastating nationally as black-grass has been in recent years,” Tom concludes.