Published on 6th February 2021

Pest Management

The adoption of biological crop protection agents: Protecting crops, naturally

The number of biological crop protection agents gaining new authorisations now out-numbers that for synthetic compounds but successfully integrating them into a programme remains a work-in-progress for growers and manufacturers.

The number of biological crop protection agents gaining new authorisations now out-numbers that for synthetic compounds but successfully integrating them into a programme remains a work-in-progress for growers and manufacturers.

Across the arena of crop protection all manufactures are striving to identify new ways of controlling established and emerging threats. Whether they be pests, diseases or even weeds, the role of conventional crop protection agents in managing these problems is being reviewed.

The need for new approaches and solutions is being led by regulators. Elected officials expect the next product to be biological and are shaping the regulatory process to support their development. This applies to all sectors, but top fruit is at the forefront of this wave: the number of new products coming to market based on biological substances now exceeds those containing synthetic compounds.

There will be some for whom this arouses fear and concern when we would rather see intrigue and enthusiasm. Such reluctance to embrace these new products is perhaps to be expected. The novel plant protection products of the past did not always meet expectations or marketing hype.

There are of course, good reasons for this poor experience. Users did not always understand what set these products apart and so did not adapt their processes accordingly. As manufacturers we must accept that in the past our understanding of their limitations or how they should be used for best results, was less than complete. For all of us in the sector, biologicals have been a learning curve, but there is no going back.

Incorporating biological products in a programme is not a simple process; it is far more than a simple substitution exercise. A changing climate is also making what was already a complex task more difficult. Pests and diseases that were once restricted by climate to a region or country are spreading further afield. Pests such the Grape Phylloxera, an aphid of grape vines that was introduced to Europe in the mid-1800s from America, has since spread north from Spain to attack pear orchards. It is a gateway pest for disease and virus that are only later detected once the crop is in store.

There are other examples. The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Halyomorpha halys), a species of shield bug that is native to east Asia is now widely found in orchards across Great Britain and the Benelux countries. It causes severe damage to a range of fruit including citrus, apple, pear and peach, and protected vegetables such as tomato, green pepper, and beans.

It is harder to control than other shield bugs, such as the Forest Bug (Pentatoma rufipes) because, like the Green Shieldbug (Palomena prasina), it is only at the nymphal stage in June and July. This makes contact-only insecticides such as FLiPPER (fatty acids) and, regulatory authorisation permitting, Sivanto prime (flupyradifurone) suitable, but also underlines the need to be accurate in application when the trees are in full leaf.

The list of pests continues. Spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) continues to spread northwards while secondary pests such as weevils (Anthonomus spp. and Rhynchites spp.) are a perennial threat. Another new arrival, Janus compressus, a species of stem sawfly once restricted to Italy, has been found in orchards across England. The larvae feed on the shoots of pears and occasionally apples, medlars and quince causing damage similar to that inflicted by shoot-cutting weevils.

Developing an integrated response

The spread of new threats, however, is only a small part of the crop protection equation. Add in the absence of products that could once be relied on to deliver comprehensive control against a pest or disease, and the size of the task confronting growers becomes clearer.

Viewed in this context, crop protection strategies will become increasingly complex and carry a greater risk of failure. How and when biological agents are used will be central to achieving the desired result, but growers must appreciate that they do not offer the same level of protection as the conventional products, typically 70% efficacy compared with 90% for synthetic compounds.

As a manufacturer Bayer is clear about all aspects of biologicals from how they can promote the sustainability of our industry to the limits of their performance and how strategies need to evolve to support efficacy. To be clear: biologicals work differently and require a change of approach. We are not hiding from this, but we are yet to see this reality accepted by the majority of users.

Developing our understanding of the factors affecting the performance of biological compounds will also involve research, specifically into how performance can be influenced by the environment. We already know that in many situations biological compounds perform best when applied in the cooler times of the day, but it is a feature of the early morning for there to be a dew. Even a light dew can add the equivalent of several hundred litres of water per hectare to the applied water rate. The effect of this can be significant when considered against what we know about optimum water rates.

Product formulation is important too. Many biologicals are living organisms so need to be held in a solution that sustains them. Then, when applied, the product needs to be retained on the leaf and not degraded by ultraviolet light. Bayer has made researching this area a priority.

New innovations such as shadow maps, which identify where the dew can be expected to stay for longer, are proving useful in helping us to develop our understanding of this area. As we acquire this knowledge, we will build on these predictive tools with satellite and drone imagery to give a better view of pest and disease build up.

It is also likely that we will complement crop protection with the wider adoption of strategically located plants that serve to as an early warning system for disease or pest pressure. We may even find ways to block the progress of a pest or disease across the landscape. Advanced systems such as these coupled with broader thinking at the landscape level will lead to an integrated response that recognises the limitations of biological substances and supports their contribution to performance.

Modelling pressure to inform strategies

A more immediate development available to growers involves using historical data to model pressure. This type of hybrid forecast allows the better performing products to be retained for use at strategic times in the protection calendar.

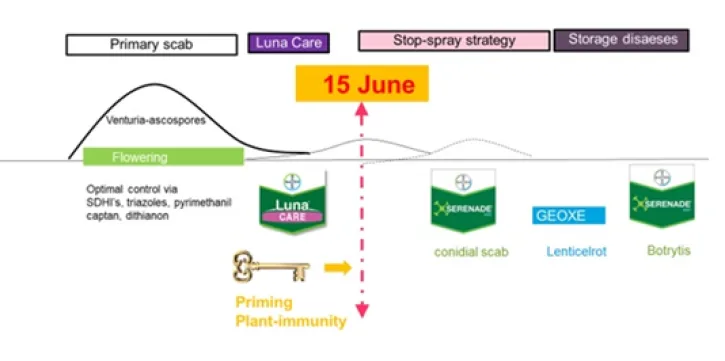

An example of a strategy that has been three-years in development, is what Bayer calls the ‘15th June strategy’. For use in apple orchards in continental Europe, modelling suggests that this is the time, in a typical season, when disease pressure falls to a level that can be managed with biological compounds.

In the case of apple scab this strategy to work the final fungicide applied before the 15th June has to be of a product recognised to give long-lasting protection, such as Luna Care (fluopyram) [not yet authorised for use in the UK] which has been shown to give up to six weeks protection under typical conditions. This strategy is undergoing field testing and will be refined further before being promoted to the wider industry.

This model is for apple orchards, but the principle can be applied to all crops where the threats come in waves.

How do biologicals differ?

Many biologicals are based on live bacteria, but there is often as much variation between strains as there is within. Sonata and Serenade ASO, for example, both contain live bacteria, but different strains with each having a different mode of action, yet in some crops they can be used to manage the same disease, such as powdery mildew in strawberries for example.

Sonata (Bacillus pumilus strain QST2808) works on enzymes whereas Serenade ASO (Bacillus subtilis strain QST 713) seeks to build a protective layer across the surface to which it is applied that repels pathogens.

Sonata works with the dew, so should be applied in the early morning or evening. In contrast, Serenade ASO needs a high-water rate to support coverage, typically 500 litres/ha, but applying when the plant is covered in dew would result in significant run-off, unless it is taken into consideration.

Golden rules for biological performance

Use them in alongside conventional plant protection products

. Biologicals products should be used when the pest or disease pressure is low thereby allowing the stronger conventional products we have left to be utilised in periods of high pressure.

Use biological products as part of an integrated programme.

Devise a strategy that incorporates the full spectrum of plant protection products. Using biologicals effectively is as much about understanding when to use other components of a programme or the potential for the plant to defend itself naturally, as it is about the limitations and advantages of biological sprays.

Take Stemphylium as an example, it only succeeds in infecting the target when the plant is under stress. Limiting the opportunity for stress through a holistic approach that considers nutrition, including the use of bio-stimulants in promoting nutrient absorption, especially calcium, alongside protection will reduce plant stress and result in less incidence of disease.

Focus biologicals where they can make the greatest contribution to crop protection

. A product’s mode of action should be considered as much as the disease to be managed when positioning biologicals in a programme.

For example, Lipopeptides, such as those in the bacillus subtilis contained in Serenade ASO, work best when the spores of the disease fungi are sporulating. Lipopeptides are derived from the soil, but in many cases are applied to leaf tissue which is distinct from their natural environment. To be effective, they must be applied in advance of the spore germination occurring which means before disease is visible to the naked eye.