While much of the focus of CSFB management is on early crop survival, minimising the damage from larvae is at least as important an imperative – both to ensure a profitable crop and to reduce future pest problems.

Author

| 14th May 2020Tags

How OSR drilling date will influence cabbage stem flea beetle attack

While much of the focus of CSFB management is on early crop survival, minimising the damage from larvae is at least as important an imperative – both to ensure a profitable crop and to reduce future pest problems.

“We have to get the crop established, but it also needs to be profitable,” insists ADAS crop physiologist, Dr Sarah Kendall. “So, we must avoid falling into the trap of being happy to get through the autumn storm and to harvest anything much at all.

“We can’t afford to throw key elements of best management practice out of the window in dealing with flea beetle either. Otherwise, we’ll end up with difficult-to-manage canopies and crops that will always struggle to deliver the yields that make them worth growing.

“Instead, we have to integrate the most useful CSFB cultural controls carefully into the most productive management regimes. If this means changing when or how we establish the crop or manage it we must adjust other elements of our agronomy to fit.”

Such an approach is especially crucial given the findings of the detailed analyses of 14 years of data from more than 1600 sites undertaken by ADAS with Bayer and other industry partners in a four-year AHDB-funded integrated pest management project concluded this spring.

This analysis shows sowing date as the only grower-controlled factor having a significant effect on the pest. Unfortunately, though, the relationship is nowhere near as simple as many have assumed.

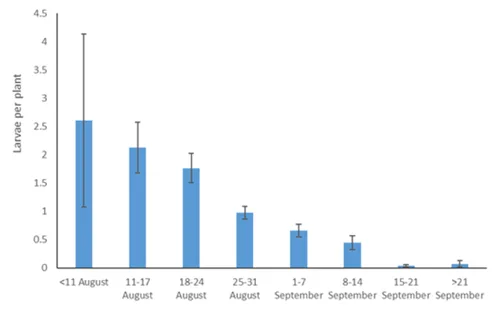

“Our modelling confirms August drilling minimises adult damage,” explains ADAS entomologist, Dr Sacha White. “However, it also shows the earlier the sowing the greater the larval burden is likely to be; mainly because of the amount plant growth available to support adult feeding and egg-laying over an extended period (Figure 1).”

Dilemma

This presents a serious dilemma. Sow earlier and you are more likely to have a crop. But you are also more likely to have a crop full of larvae that yields poorly and may have to be abandoned later in the season.

Alternatively, sow later to minimise the larval challenge and risk not being able to establish a viable crop because it emerges into higher levels of flea beetle activity and is far more vulnerable to adult grazing.

“It’s not an easy decision,” Dr Kendall agrees. “On balance, I favour sowing later because, if I have to, I prefer replacing a crop before investing too much time, effort and money in it.

“We also know from experience that, even on heavy ground in East Yorkshire, it’s perfectly possible to bring in over 4.5t/ha from mid-September sowing at 26 seeds/m squared with the right combination of variety and early crop management.

So, what strategies does ADAS evidence and experience suggest might be valuable for earlier and later sowing – or indeed both?

Well, Dr White and Dr Kendall insist that drilling into moisture – rather than the hope of it – is fundamental. As are good seedbed conditions, a consistent sowing depth and effective rolling for maximum seed-to-soil contact.

More than anything else, perhaps, this means knowing when not to sow OSR and – again like black-grass management – having enough rotational flexibility to sow something else instead.

The ADAS analyses show no benefit from increasing seed rates. There is a tendency for higher seed rates to reduce percentage leaf loss, and they definitely result in higher plant populations. However, seed rates appear to have no discernible effect on larval numbers per plant. Higher sowing rates, therefore, simply mean more larvae per field.

“While higher seed rates with farm saved seed may help crop survival, we generally find little yield benefit from rates of more than 40 seeds/m squared,” reports Dr White. “Add the extra risk of weaker plants, the danger of less productive canopies and the risk of higher pest populations for the future, and we really wouldn’t advise pushing-up rates.”

Interestingly, the analyses suggest a tendency for less beetle damage with declining intensities of cultivation; a finding supported by a recent BASIS project revealing markedly lower larval numbers in direct drilled crops, but one needing far more investigation before any firm conclusions can be drawn.

As yet, ADAS also has insufficient science to support companion cropping. However, their studies across several sites over two years are showing that delaying the control of volunteer OSR from the previous season can give significant reductions in adult numbers, feeding damage and larval populations in neighbouring crops (Figure 2).

“This technique has obvious promise because we know flea beetles use the breakdown products of glucosinolates produced by OSR to locate crops and can’t distinguish between planted crops and volunteers,” Dr White points out. “Once they’re feeding and mating their wing muscles weaken, making them much less mobile, so they’re trapped.

“To be effective in diverting flea beetles from planted crops, our trial work shows the volunteer trap crops need to be close by and left green until late September. This can take valuable pressure off OSR crops at their most vulnerable stage, and would fit particularly well where wheat crops are being drilled later in the battle against grassweeds.”

Winter defoliation

Another technique showing promise for larval control, in particular, in ADAS work is winter crop defoliation – either by cutting or with sheep grazing. Drastic though this may be, both plot trials and field-scale investigations have resulted in significant reductions in larvae.

“Providing the defoliation is ahead of stem extension and spring growing conditions are reasonable this can be done without significant yield loss,” says Dr White. “To be safe, I’d always defoliate before the end of January. I’d also only do it with a well-established crop, so it’s probably more suitable – as well as necessary – following earlier drilling. And I’d want a variety that was especially vigorous in its spring growth.”

Whatever approach is taken, Dr Kendall insists it’s essential to have a firm and well-integrated strategy that marries key elements of flea beetle management carefully with established best OSR growing practice.

“Earlier drilling, for instance, needs to be accompanied by much more focus on controlling larvae and spring canopy management,” she urges. “It’s also likely to require varieties with particular resistance to phoma and light leaf spot and first-class standing ability; plus a careful watch-out for early season pests like cabbage root fly.

“Equally, drilling later will put the onus on the most vigorous, fastest-developing varieties; particular attention to seedbed conditions and management; and, a spring programme involving earlier nitrogen, sulphur and low rate PGRs.

“In our experience healthy, well-structured soils with good levels of organic matter make all the difference in dealing with the extra risk that flea beetle brings,” concludes Dr Kendall. “They are as important as any other single element of an integrated pest management approach.”

Figure 1: Relationship between drill date and CSFB larval populations in the autumn.

Source: ADAS, 2020; AHDB-funded CSFB IPM project

Figure 2: Mean numbers of adult CSFB caught in yellow water traps in new OSR crops adjacent to a field in which vOSR had been controlled early or late

Source:Non-chemical control options for cabbage stem flea beetle in oilseed rape.

S White, S Ellis & S Kendall. Aspects of Applied Biology 141

Cabbage Stem Flea Beetle Solutions

Our resource identifies the most promising ways to Battle the Beetle and ensure OSR remains a key part of your combinable crop rotation.

Cabbage Stem Flea Beetle Solutions