Drilling winter wheat later is a standard recommendation to control black grass and Italian rye-grass. In benign autumn weather conditions, it is proven to work. Unfortunately, if like 2023, there is prolonged wet weather from October onwards, the consequences may be poorly established crops and undrilled fields.

Author

| 27th June 2024Tags

Early or late: the great drilling debate

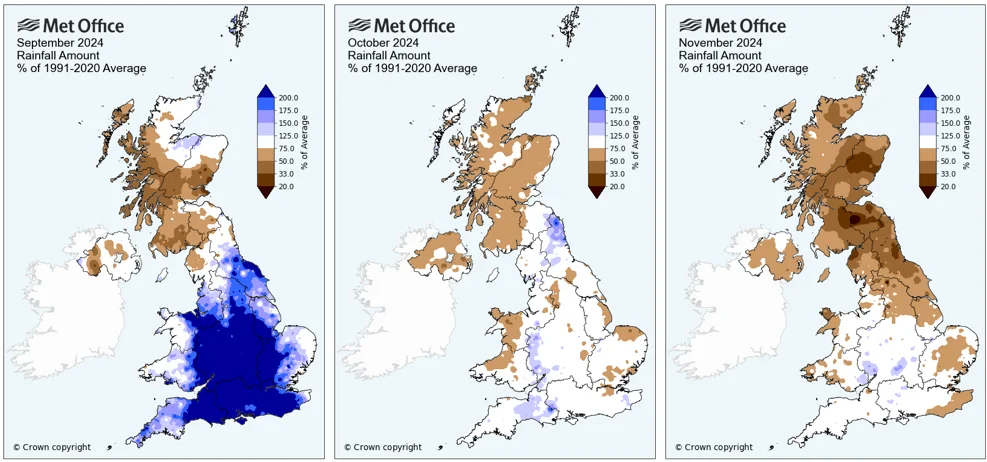

Situation following autumn 2024

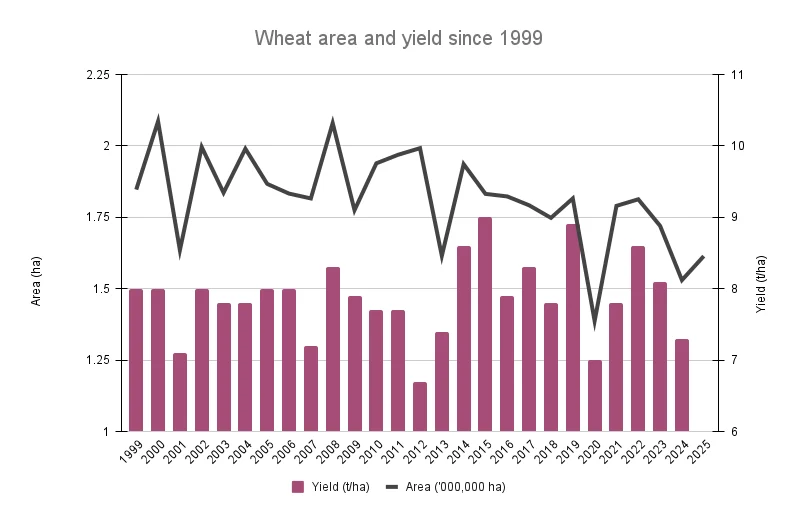

In 2024/25, the total wheat area stands at 1,614,000 ha according to the AHDB Early Bird Survey. This marks a small increase from the previous season but is still lower than the long-term average of 1.8 million ha. For reference, the wheat area fell to 1,387,000 ha after the particularly bad autumn of 2019.

After a disrupted autumn, there is an understandable tendency to drill earlier the following year to ensure there is wheat in the ground. But with grass-weeds, particularly black-grass and Italian ryegrass a persistent problem on many farms how to strike the balance between drilling at the economic optimum and the weed control optimum?

Economic optimum

Drilling in mid–late September is generally considered optimum time for maximising yield in wheat crops. Crops have time to become well-established before winter and are better able to cope with difficult weather conditions.

Analysis of 82 Recommended List trials in Eastern England from 2010–14 showed a 0.27% yield loss for every day drilling is delayed after 1 September in a weed free situation with no other agronomic issues. This would mean an 8.1% yield loss from delaying from 20 September until 20 October, equivalent to approximately 1 tonne/ha in a typical wheat crop.

There are also the psychological and practical benefits to completing drilling. Having a confirmed area of wheat makes it easier to plan any spring cropping and forward sell crops if the prices are favourable. It also frees up time in autumn to focus on other tasks. But if weed populations are high, any peace of mind is illusory because weed control will become a drain on time and money until harvest.

We Highly Recommend:

The main germination period of black-grass and Italian ryegrass tends to be from late September until mid-October. The aim of delaying drilling is quite simple, to plant wheat after the main flush of weeds to avoid significant germination in the crop.

Black-grass germination pattern

Italian ryegrass germination pattern

In trials for AHDB Project Report 560, delayed sowing of winter wheat by three weeks from mid/late-September to early/mid-October reduced black-grass infestations by 33% on average while, delaying until late October/early November reduced plant counts by 62%. In addition, heads and seeds per plant, were reduced by an average of 49%. However, there was quite a large range in the results showing that field and weather conditions, particularly soil moisture, have a large influence.

Any delay in drilling means fewer weeds germinating in the crop. If putting off drilling until mid-October seems risky, delaying by as little as one week could still mean less germination in the crop.

The same study noted an additional 26% control from pre-em herbicides (240 g flufenacet h + 60 g diflufenican + 1600 g prosulfocarb per hectare) when applied to October drilled crops compared to September. Hence some of the benefit of delayed drilling is linked to herbicide performance. Increased soil moisture aids the performance of mobile actives like flufenacet, and cooler, shorter days slow down the degradation of herbicides meaning there is a longer residual effect.

The same study found that 100 black-grass heads /m2 causes 1.08 tonnes of lost yield. Black-grass typically has 5–10 tillers, meaning that plant counts of 10–20 /m2 are enough to lose more than 1 tonne in yield. Previous research from the mid 1990’s arrived at a similar conclusion that 25 plants /m2 would result in a 10% yield loss on average. Hence any potential yield gain from early drilling can easily wiped out by increasing numbers of grass-weeds in the crop. There is also the long-term dimension of higher seed return which will cause more problems for future seasons.

Table: Black-grass yield penalty (Taken from S. Moss 2013 Everything you wanted to know about black-grass but didn’t know who to ask)

Source: AHDB Project Report No. 560 July 2016 Sustaining winter cropping under threat from herbicide resistant black-grass

Red triangles = outlier values due to poor crop establishment.

It’s interesting to compare drilling date trial results with long-standing advice about black-grass control. A 1969 MAFF leaflet states: ‘At Rothamsted Experimental Station, sowing wheat before 25 October has led to an increase in black-grass; sowing between 25 October and 5 November did not affect the infestation but sowing after 5 November led to a decrease.’

The drilling dates all seem quite late by modern standards, but the research comes from the 1960s before the varietal changes that increased yield and the introduction of many herbicides in the 1970s and 80s. But still food for thought on how difficult control could be without herbicides.

Population dynamics

Is the size of the weed seedbank increasing or decreasing? That is the most important question for assessing long-term viability of weed control. This needs to be an assessment across the entire rotation rather than just one cropping season because some crops are inherently harder for grass-weed control. In general, spring crops and forage crops can reduce weed populations whereas for most winter crops it’s a case of keeping a lid on things.

Each head of black-grass produces between 50–200 seeds, but 100 seeds is a reasonable average (and easy to calculate with). Just 10 black-grass heads /m2 could produce 1000 seeds that reach the seedbank to cause problems next season. Hence, even apparently quite small differences in control levels can lead to substantially different levels of seed return.

BYDV

Delaying drilling into October helps manage the risk of aphids transmitting BYDV. In cooler weather, it takes longer for the second generation of aphids to emerge which tend to spread the disease. The T-sum calculation for targeting pyrethroid sprays is aimed at controlling the second generation.

Warm September weather can mean the necessary degree days quickly accumulate to warrant a BYDV spray which could result in two or three sprays in the season which is a practical challenge and not an ideal step for resistance management and sustainability.

There is no simple answer to the question ‘when is the best time to drill?’ The most important thing is to have a plan based on a field-by-field assessment and a also a plan if things go wrong.

Whenever drilling starts, drill in order of weed pressure so the worst fields get drilled last. This provides a better opportunity for weed control this season and if the worst happens and there is a wash out, they can go into a spring crop.

Avoid drilling early in high weed pressure fields as any infestations will likely make the crop unviable. Having to write off and redrill any crop is a significant cost and effort, negating the perceived benefits of early drilling.

Ensure there is sufficient moisture in the seedbed for establishment and pre-em performance. Seedbeds were very dry in autumn 2022 which led to indifferent crops and weed control on some farms. Of course, this is a moot point if there is a repeat of summer 2023.

Benefits of later drilling:

Better opportunity to use a stale seedbed + Roundup to eliminate weeds

Fewer weeds germinating in the crop

Fewer heads per plant

Lower seed count per head

Better pre-em performance

Reduces BYDV risk

Benefits of drilling early:

Guaranteed area of winter wheat for harvest. Crops will be well established before any serious wet weather.

Increased yield potential yield.

Peace of mind