Published on 1st August 2022

Disease Management

Changing disease pressure in sugar beet: Less powdery mildew, more rust and Cercospora

In sugar beet - rust (Uromyces betae) has displaced powdery mildew (Erysiphe betae) as the principal threat while milder autumns mean that Cercospora leaf spot (Cercospora beticola) has emerged as a serious threat to late-lifted crops.

The nature of the disease threat facing sugar beet crops is evolving. The reasons for this change are thought to be a result of a combination of factors. The diligent use of fungicides is thought to have gradually reduced the inoculum levels of certain diseases caried over between seasons. A warming climate has created conditions that favour diseases that were previously less of a concern while the introduction of varieties with better disease resistance has seen crops able to withstand greater pressure before succumbing.

In practice, this means rust (Uromyces betae) has displaced powdery mildew (Erysiphe betae) as the principal threat while milder autumns mean that Cercospora leaf spot (Cercospora beticola) has emerged as a serious threat to late-lifted crops. Stemphylium, a disease more associated with continental crops, has come to be found at low levels across all factory areas of Great Britain. As our climate continues to warm, both Cercospora leaf spot and Stemphylium are expected to become greater threats to crop performance.

The 2020 calendar year is perhaps an apt illustration of how climate is changing the nature of disease pressure.

Met Office data for East Anglia reveal that 2020 was the second warmest year on record (records began in 1836) with a mean annual temperature of 11.23°C. This is 0.7°C higher than the 30-year average for 1991-2020 of 10.5°C. Only 2014 was warmer with an annual mean of 11.45°C.

Rainfall in East Anglia during 2020 was also higher than the long-term average. Above average rainfall in the winter, summer and autumn more than made up for a drier-than-average spring to make 2020 the eighth wettest year in the 1991-2020 period at 697mm.

Bayer fungicide trials from recent seasons, highlight the disease pressure facing crops has changed. The dry spring meant disease came into crops later than in a typical year.

In the untreated plots at Bracebridge, Lincolnshire, rust was not detected at being above the 5% threshold for fungicides until mid-September. This contrasts with when it might otherwise be expected to manifest in July. No powdery mildew or ramularia were detected at all. Cercospora leaf spot increased rapidly from less than 2% in mid-September to more than 17% in October.

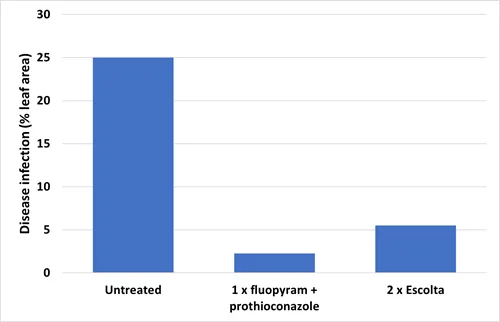

In contrast, powdery mildew did affect plots in the trial at Claythorpe Heath, also Lincolnshire. From 0% in late July to 10% of leaf area a month later to 26% by 21st September. Rust was not detected until late October. Cercospora leaf spot was first detected at the September timing and again in October. Both were at low levels. By early November, it had spread rapidly to affect 25% of the plants in the untreated (see chart).

Cercospora leaf spot incidence and control in 2021

Reference: Bayer trials, Caythorpe Heath. Assessed on 9th November 2021.

What can we learn for this season?

Seasonal conditions will determine when and to what extent disease affects crops and it will also influence which disease has the greatest impact on performance, explains Antonia Walker, Bayer campaign manager for roots.

“It seems no two seasons are ever the same so vigilance will be needed if growers are to ensure fungicides are well-timed,” Miss Walker says.

“Despite the evolving situation, the strategy promoted over the past 15 years remains the best course of action. In most years, crops should be inspected for signs of disease from early July with the first fungicide applied as soon as symptoms occur, and a second spray applied about four weeks later.

“Where crops are to be lifted after the end of October, a third fungicide should be applied after 1st September, especially where Cercospora leaf spot is expected to be a threat,” Miss Walker adds.