Soil dwelling nematodes are a serious threat to crop performance. They affect a range of crops including potatoes, carrots, cereals, raspberries and strawberries, both directly and indirectly often inflicting severe economic losses.

Soil dwelling nematodes are separated into migratory (free-living) and sedentary types. Sedentary types such as cyst nematodes (Globodera species) are characterised by being permanently attached to the roots of their host plants once they start to feed and reproduce. Conversely, free-living types, such as needle nematodes (Longidorids), stubby-root nematodes (Trichodorids) and root-lesion nematodes (Pratylenchids), move freely through the soil between feeding bouts. While the two types often co-exist, the presence of one is not dependent on the other.

The damage they inflict is directly dependent on the size of the population present and their impact can be exacerbated by other organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, invading the root via the lesions caused by nematodes. For instance, there is a well-documented relationship between the density of PCN present in potato roots and the incidence of stolons infected with Rhizoctonia solani and the level of stolon pruning and stem canker.

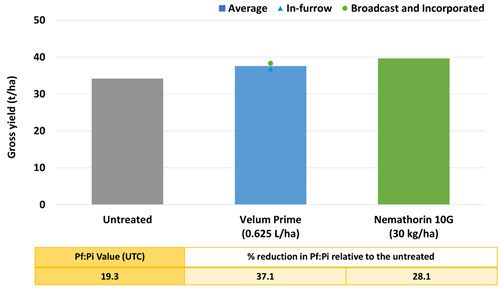

In the case of potatoes, PCN-affected plants show early stage damage through reduced vigour and stunted growth which leads to reduced light interception. Ultimately, this leads to lower yields through variations in dry matter and tuber size.

The extent of any impact is largely determined by the level of infestation. For G. rostochiensis, yield losses of up to about 20% and 70% have been observed for populations of 8 and 64 eggs per gram of soil respectively. Infestations of G. pallida cause similar symptoms to G. rostochiensis, but the impact is more serious with a quoted damage threshold as low as 1 to 2 eggs per gram of soil. The impact of free-living nematodes is harder to gauge because populations and infestation levels are more heavily influenced by soil type, environmental conditions, cropping history and the variety planted.

Tackling nematode populations is far from easy and no single action will deliver the 98% effective control needed to prevent a population increase. To succeed, a combination of measures including cultural and chemical controls is required. Here we consider some of the measures available to growers and their contribution to control. The steps that follow assume soils have been tested to identify species and population density with areas of infestation mapped.

Key steps:

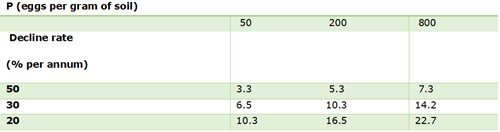

Follow a long rotation

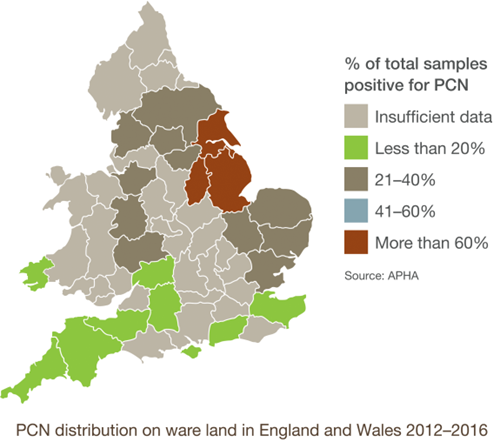

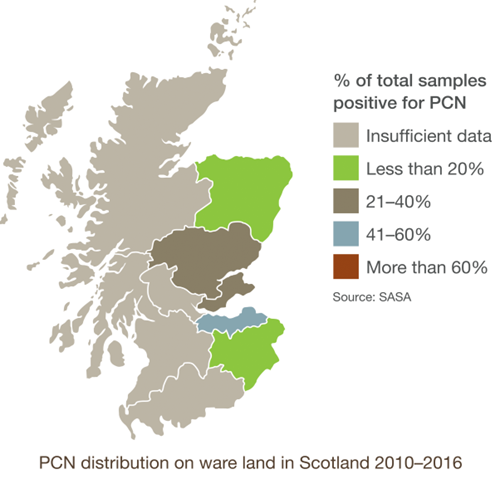

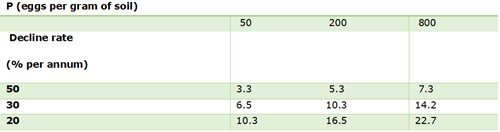

Research indicates that once PCN has been detected it can remain viable in that soil for at least 40 years, but that spontaneous hatching even in the absence of potatoes means there is a natural rate of decline. This is reckoned to be at its greatest in the first 10 years. Consequently, the AHDB suggests rotations of at least 6.5 years as a necessary first step to successfully managing populations. Rates of decline, however, vary depending on the species present and soil type while incorporating other methods of control may improve rates of decline, so management should be devised on a field specific basis.

View Table

Reproduced from AHDB Potatoes 1240001 FINAL Report

Adopt good field and machinery hygiene

PCN can be spread from field to field through various means including wind, flood water, other plants, machinery and wild mammals and yet good machinery hygiene is considered a valuable means of control. Doing so may also help limit the spread of other undesirable weeds, pests and diseases such as black-grass seeds and the brassica club root bacterium.

The AHDB, notes that “all waste, soil and by-products from potato harvesting, grading and processing operations should be disposed of in line with the Plant Health Code of Practice on Management of Agricultural and Horticultural Waste.

Those with access to commercial composting facilities may find it interesting to note that the German Biowaste Ordinance prescribes sanitation of organic waste before it can be used on arable land. Cysts of G. rostochiensis have been shown to be killed by composting for seven days at 50-55°C and by pasteurisation for 30 minutes at 70°C.

In the case of FLN good weed control is vital as common species such as field pansy, knotgrass, groundsel, shepherd’s purse and chickweed can act as hosts for tobacco rattle virus (TRV) which causes the disorder known as ‘spraing’ and is transmitted by stubby root nematodes.

Use resistant varieties

The use of resistant varieties is considered one of the most effective ways to suppress PCN multiplication. Similarly, if FLN are a burden, choose a variety that doesn’t exhibit the spraing symptoms of corky rings in the tuber flesh.

The AHDB Potato Variety Database is an easily accessible index of varieties describing a broad range of features and characteristics including susceptibility to Globodera species and spraing.

Plant only certified seed

The growing of seed potatoes in the UK is subject to the PCN control directive which was introduced to keep clean land free by reducing the risk of growers planting seed from infested stock. Farm-saved seed in Scotland is subject to similar restrictions, but not the rest of the UK. Those outside Scotland who choose to plant farm-saved seed should ensure that it has been produced in accordance with the Seed Potato Certification Scheme.

Consider biological measures

Trap crops and bio-fumigants have long been promoted as representing a sustainable means of tackling PCN while simultaneously offering a means of protecting soils overwinter and/or as cover crops for wild mammals.

Positive results have been observed with trap crops such as Sticky Nightshade (Solanum sisymbriifolium), a non-tuber bearing solanaceous plant, that appears to effectively stimulate PCN hatch while preventing it from reproducing.

Research suggests it can reduce PCN by up to 75% within one season, is easy to destroy, tolerant to frost and doesn’t get blight, but its promise needs to be tempered. The downside is it needs to be sown into warm soils (above 8°C to emerge) and requires a full growing season to reach the 700g/m2 of dry matter needed to be effective. You also need to consider the effects on soil-borne diseases they may be hosts for. Furthermore, it is reasonably expensive with a 2015 estimate suggesting it costs about £550/ha.

Similarly, bio-fumigants such as mustard sown in the autumn and incorporated ahead of planting have shown similar promise.

Research has found that PCN mortality is increased after exposure to hydrolysed glucocinolates which release volatile isothiocyanates (ITC), a form of mustard gas. Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) has been found to be higher in the derivatives 2-propenyl-ITC and 2 –phenylethyl-ITC and studies suggest egg viability can be reduced by up to 40% depending on the accumulation of biomass prior to maceration and incorporation. The exacting nature of the maceration and incorporation process needed to achieve the desired control, however, means that as with trap crops these are still a work in progress for most growers.

Further Reading