Loss of Neonicotinoid Seed Treatments in the UK

Following in 2018 ban of seed treatments here are some resources to help to grow crops without these valuable seed treatments

Following in 2018 ban of seed treatments here are some resources to help to grow crops without these valuable seed treatments

Effective stewardship is crucial to demonstrating our professional and responsible use of seed treatments and follow-up sprays. Simply, we must all handle products carefully and according to recommended guidelines – and be seen to be doing so.

Bayer has produced a number of free resources to help you. To get yours, click here.

Directive 2010/21/EU Part A restriction. For the protection of non-target organisms, in particular honey bees and birds, for use as a seed treatment:

Seed treatments are so simple to use, it is easy to forget that they are pesticides and that sowing seeds needs the same care as spraying pesticides. Cereals seeds pose a special risk because they are a potential food source for many birds and small mammals. On farm, the main risks come from:

Avoid dust

Avoid spills

Cover all seeds

Care after drilling

Click each image or text link to download these files.

Establishes a healthy yield by providing all-round protection from major seed- and soil-borne diseases in your winter wheat.

Find out more

For Suffolk farmer James Black the threat of losing neonicotinoid seed treatments in sugar beet, a non-flowering crop with no appeal to bees, smacks of nothing less than prejudice towards farmers and ignorance of modern farming.

For Suffolk farmer James Black the threat of losing neonicotinoid seed treatments in sugar beet, a non-flowering crop with no appeal to bees, smacks of nothing less than prejudice towards farmers and ignorance of modern farming.

“The portrayal of farmers as destroyers of the environment is an attack on farmers and farming, it is born out of ignorance and prejudice. It demonstrates a worrying trend in political circles where decisions are being made by both elected and non-elected Eurocrats with a poor appreciation of the situation and the realities of food production. There is little recognition of the work our industry does to promote the environment, the professionalism of growers in using plant protection products or even of the demanding regulatory hurdles these products must pass before being receiving authorisation. I question the instigation of this proposal and am concerned that a ban, were one to be implemented, would be the result of nothing more than preconceived misconceptions. This has been fuelled by the effective lobbying of a group of well-organised environmentalists intent on pushing their own agenda, rather than the judicious use of science,” says Mr Black.

Mr Black farms about 1200 hectares in mid-Suffolk and runs an outdoor pig enterprise consisting of 600 sows. The farm employs a four-year rotation consisting of two break crops and makes effective use manure to maintain soil health. The business actively pursues environmental goals, with targeted enhancement of the countryside to promote a viable habitat for all animal species. But the potential loss of neonicotinoid seed treatments in both sugar beet and cereals irritates him because, he says, there is no firm evidence to support it.

“At about 60 grams of active substance per hectare, seed treatments represent the safest and most targeted means of controlling virus-carrying aphis we have.

He cites his experience with oilseed rape since the moratorium on neonicotinoid seed treatments was introduced [in this crop] in December 2013. “Our use of insecticides has increased about 150% compared with what we used in 2010 simply because of the limited efficacy of the alternatives. As products are withdrawn and resistance increases to those that remain, I become increasingly fearful for the future of our industry,” he adds.

In sugar beet production, the seed is treated with a coating of one of two neonicotinoid products to confer protection against virus-carrying aphids for up to 12 weeks, after which the plant can withstand attack.

The principal threat during this period is from virus yellows, a group of viruses that attack the leaves causing considerable yield losses, up to 50% if infection is early.

The main vectors of virus yellows are the peach-potato aphid (Myzus persiace) and the black bean aphid (Aphis fabae) and the risk of early and severe attack is greater following a mild winter and warm spring as these conditions favour aphid multiplication.

“In the absence of a hard winter, crops would be under pressure from the outset without protective seed treatments. Their loss would threaten the long-term future of the industry and for many growers, including myself, sugar beet would become a risky and ultimately, untenable crop,” says Mr Black.

The European Commission has recently proposed an extension on the ban of neonicotinoids from oilseed rape, to all field crops. This ban would have significant consequences for the majority of farmers growing 16 million tonnes of wheat, 7 million tonnes of barley and 7 million tonnes of sugar beet in the UK each year.

The European Commission has recently proposed an extension on the ban of neonicotinoids from oilseed rape, to all field crops. This ban would have significant consequences for the majority of farmers growing 16 million tonnes of wheat, 7 million tonnes of barley and 7 million tonnes of sugar beet in the UK each year.

The proposed ban appears to disregard the implications of further limiting farmers’ crop protection tool kit and the subsequent challenge of resistance management for pests, for which few alternatives are available.

Contract farming over 3,600 hectares in the Scottish Borders, David Fuller of McGregor Farms is extremely concerned about the effects this ban would have on the 14 farms he is responsible for.

Mr Fuller uses Deter (clothianidin), a neonicotinoid, to dress 60% of his wheat, and all his barley seed, to protect against slugs and aphid vectors of BYDV. He begins:

“Unlike further south where wheat is drilled late to manage black-grass, up here we have to drill early, as once the narrow window to drill is closed, that’s it. Due to the damp summers we have, slugs can be a real issue and we find that Deter covers us from grain hollowing.

“With aphids flying later into the year, we also use Deter to provide protection against BYDV. If we were to lose Deter, there’s no doubt we’d have to use more insecticide sprays to counter the loss, but that also depends on the weather being good enough to get out and spray. If it isn’t, the crop will go unprotected, which could be disastrous for yield come harvest.”

Mr Fuller makes the point that many of the crop protection products used by growers can be found in your local supermarket or garden centre. Of course, on a farm these products are used on an industrial scale, however the targeted nature of seed treatments, means they are much more environmentally friendly than their spray and pellet counterparts, he says.

Claire Matthewman, Seed Treatment Campaign Manager at Bayer, agrees. She adds:

“If growers were to lose Deter there would undoubtedly be an increase in broad spectrum insecticide sprays to counter the seed treatment activity in this area.

For those growers using Deter to counter aphid vectors of BYDV, we’d estimate that an extra 1-2 million hectares would have to be sprayed with pyrethroids to equal its effects – that’s the equivalent of the top 250 stadiums in the UK being sprayed every day for 11 years! Pyrethroids are not as targeted an approach as a seed treatment and aphid resistance will only increase given a couple of seasons without Deter.”

Mr Fuller concludes:

“It is important to remember that we are trained professionals that take stewardship seriously and behave responsibly when using seed treatment products.”

“We must follow the science. If neonicotinoids are proven to be harmful to bees then we can’t bury our heads in the sand. But in the same vein, we can’t remove another essential element of the tool kit without reasonable evidence.”

Following the ban on neonicotinoids in oilseed rape in December 2013, the European Commission has recently proposed to extend the ban across all field crops.

Following the ban on neonicotinoids in oilseed rape in December 2013, the European Commission has recently proposed to extend the ban across all field crops.

With significant consequences for winter cereals and sugar beet, it appears that no assessment on the impact this will have on farmers has been carried out before proposing these legislative measures.

Ben Atkinson farms 6,800 acres of land in Lincolnshire and having already witnessed the effects of banning neonicotinoids in oilseed rape, he is concerned with the environmental impacts the proposed ban could have.

“Being in Lincolnshire, cabbage stem flea beetle pressure isn’t as high as it is for some of my friends in Cambridgeshire and Bedfordshire, where the impact of the pest is diabolical. Having said that, since the ban of neonicotinoids in oilseed rape, we’ve had to use more pyrethroid sprays to manage the pest.

“For the last couple of years, cabbage stem flea beetle pressure has been getting progressively worse and I think it is a ticking time bomb for everyone growing oilseed rape.”

Mr Atkinson has a six-year rotation of winter wheat, winter barley, winter oilseed rape, spring beans, spring barley and sugar beet. Four of his six crops have been or would be affected by a ban on all neonicotinoids.

Looking back, Mr Atkinson first started using Deter (clothianidin) – a neonicotinoid seed treatment – on his winter wheat as a management tool, safe in the knowledge that he didn’t need to go on with another insecticide before Christmas. However, he says that due to black-grass concerns, the use of Deter has since evolved.

“In recent years we have been drilling winter wheat a lot later due to black-grass pressure. This means we physically can’t get on with the sprayers to combat BYDV due to the ground conditions being too wet.”

For many growers, it isn’t just BYDV that neonicotinoids protect against, highlights Nigel Adam, Development Manager at Bayer. He adds:

“BYDV causes a serious problem for growers like Mr Atkinson but the other major use of Deter is against slug damage through seed hollowing and the subsequent establishment losses. We’d estimate an additional 1,600 tonnes of slug pellets would be required to equal the effects of Deter – this would be an increase of 67% in usage. This obviously isn’t as targeted an approach as a seed treatment.”

Mr Atkinson concludes that if he can’t spray against BYDV then the only alternative is to use a seed treatment.

“We have a limited number of insecticides available to us, and we have seen in oilseed rape that a ban on a seed treatment means more insecticide sprays, which of course hit the target species as well as non-target species. The seed treatment approach is a much safer way and to ban it would be shooting themselves in the foot.”

European proposals to extend the ban on neonicotinoid seed treatments to non-flowering crops highlights the disregard for science among policy makers in Brussels.

“There is no scientific reason for this proposal,” says Cambridgeshire farmer and former NFU sugar board deputy chair, Robert Law who produces roughly 20,000 tonnes of sugar beet annually. The proposal is the result of lobbying pressure by non-government organisations (NGOs), he says.

“There are environmentalists who have decided that neonicotinoid seed treatments are bad and want them banned. They’re not looking for science to support their claims, they rely on hype and hysteria,” he says.

He cites research findings published in January by the Joint Research Centre, part of the EU Science Hub, which concluded that: ‘the current neonic restrictions have resulted in farmers significantly increasing their use of insecticide sprays and other treatments. These alternatives costing more money and time and proving less effective at controlling pests with the result that pest numbers are increasing with no observed benefit to beneficial insects.’

Were the proposal to extend the ban to sugar beet and cereals to be adopted, he fears it would result in more indiscriminate insecticides being applied to the detriment of the species many are actively trying to promote.

“Part of my farming operation involves the production of some flowering crops which are attractive to bees. They support a range of bee species, including the honey bees managed by the bee-keepers that use my farm, none of which have expressed any concerns about my use of neonicotinoid containing seed treatments or foliar insecticides.

“Like me, they question this assertion that bees are affected eight months after the product is used and after which it is no longer detectable. It’s simply not something that is been borne out by their experience,” he says.

The speed at which these proposals have been presented also concerns him, as it has left little time for the case supporting it to be properly scrutinised.

“These proposals have come up on us quickly. There is talk of a possible vote on this next month. The speed of it raises questions about the role of science in European policy development. Even the EU’s own research questions the need for this ban and yet the EU Commission is proposing to extend it further into non-flowering crops. It’s a crazy situation that suggests there is a distrust of the science. It is no way to create a forum for policy discussion,” he says.

The threat of yield losses through virus infection is not restricted to sugar beet and Robert Law has seen first-hand the effect on other crops when the threat has been overlooked.

Implications for other crops too, such as control of barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) in cereals. “We use Redigo Deter on our cereal crops to confer protection against BYDV infection in the autumn. Two years ago a neighbour chose not to do the same with a crop of winter barley and the effects were catastrophic. The implications for my business were this to be a regular occurrence would be severe,” he says.

We anticipate that the proposals will be discussed at the SCOPAFF meeting next March. However, the position is far from clear.

Some Member States favour the ban; others question the proposals or want to wait for the European Court of Justice to rule on the use of neonics in oilseed rape or the full EFSA impact review on neonic seed treatments.

The UK Government has queried the timing of the proposals and the logic of basing them on a theoretical risk. Yet it is not definite that it will vote against.

Given this uncertainty, there are two ways you can make a difference:

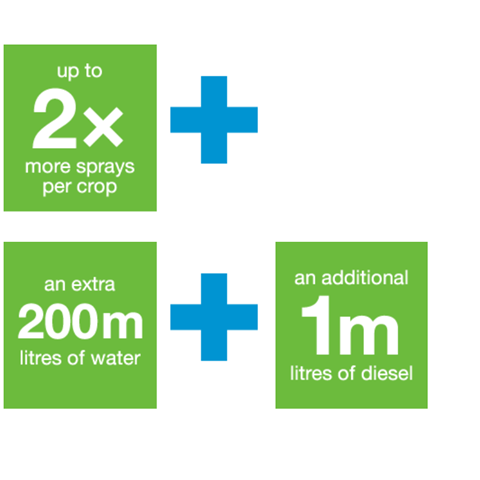

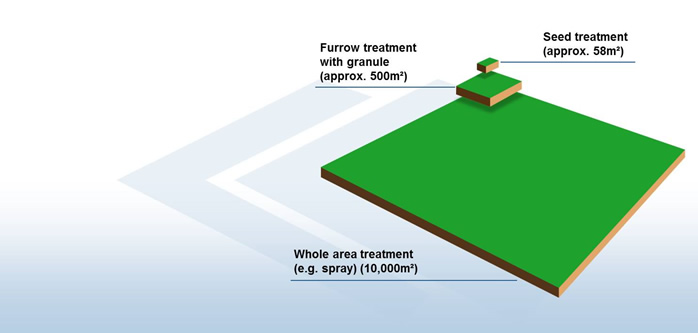

Seed treatments reduce the need to treat crops after emergence, such as with broad-spectrum insecticide sprays or slug pellets.

Seed treatments are more environmentally friendly than spray treatments which also need careful timing. Moreover, a single seed treatment may well do the job of multiple sprays.

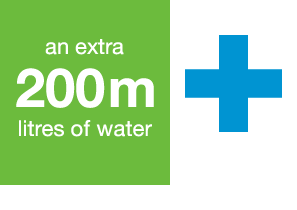

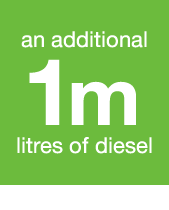

Without seed treatments farmers would need to spray cereals an extra one or two times, use an extra 200 million litres of water and an additional one million litres of diesel to power their tractors and equipment:

Using Deter seed treatments for reducing slug grain hollowing in cereals potentially saves up to 1,600 tonnes p.a. of slug pellets being used in the UK.

Without seed treatments slug pellet use will increase:

In eleven UK sugar beet field trials assessing the impact of virus yellows, Poncho Beta shows an average 20% yield increase over untreated crops. Yield losses at this level experienced in the field would have a huge impact on sugar beet production.

Bees do not forage, or normally visit, cereals or sugar beet crops. We insist on good stewardship practices within Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programmes so that farmers protect pollinators from potential risks. In their explanation, the European Commission based their proposals on a Bee Guidance document that has not been ratified by Member States.

Naturally, we are very concerned that the Commission would take far-reaching decisions using a risk assessment approach that has never been adopted, primarily due its severe shortcomings, and that it did not consider carrying out a transparent impact assessment before proposing these legislative measures.

Bayer’s position is that we are all concerned about bee health, but to propose a ban based on concerns for bees and other pollinating insects in non-bee-attractive crops is frankly bizarre. It is therefore clear that the decision to table these proposals was made without consideration of the impact that any ban would have on a UK or European farmer’s ability to grow a high-quality, affordable crop of wheat, barley or sugar beet.

Seed treatment is still the most environmentally preferable method of crop protection:

Today’s seed treatments contain low quantities of active substances, very precisely applied and highly targeted in use. The equivalent amount of seed treatment used over a 10,000m2 field, for instance, is just 58m2, without the risk of overspraying.

Bees do not forage, or normally visit, cereals or sugar beet crops.

You may be challenged about your use of neonic seed treatments. These answers should help you respond.

“Neonics should be banned because they persist in the soil”

Neonicotinoids can be found in soil after use as a seed treatment, but their persistence is well within regulatory guidelines. Their ‘bioavailability’ – whether they are taken up by and protect plants in subsequent crops – is low; if this did happen, farmers wouldn’t need to use a seed treatment every year to protect their crop. Unfortunately, subsequent crops are susceptible to pest damage.

“Only a fraction of a seed treatment is taken up by the plant”

Seed treatments are the most targeted approach to protecting plants from insect damage; they only control insects that would otherwise eat the crop, leaving those that use the crop as cover untouched. This compares to the application of a broad-spectrum insecticide across the whole field which may affect beneficial insects as well as target pests.

”Neonics accumulate in nearby plants”

One paper suggests that this could be an issue; nearby plants were found to have higher neonic levels than in the treated crop in the middle of a field of oilseed rape. We cannot rationalise this data and it doesn’t agree with previous findings. Clearly, neonic seed treatments need to be used carefully to avoid scattering treated seeds into margins – stewardship is key.

“Neonics aren’t necessary and farmers should use alternatives”

A number of NGOs made similar comments three years ago when the ban on neonic seed treatments in oilseed rape came into force. It has proved so difficult to establish the crop that the area of oilseed rape in the UK has diminished by 23% since the year before the ban – essentially we have lost one in four fields of oilseed rape.

Bayer believes that the EC proposal to restrict further the use of neonicotinoid plant protection products is illogical and disproportionate. Yet the impact will be significant. Decide for yourself from these illustrations.

Seed treatments reduce the need to treat crops after emergence, such as with broad-spectrum insecticide sprays or slug pellets.

Seed treatments are more environmentally friendly than spray treatments which also need careful timing. Moreover, a single seed treatment may well do the job of multiple sprays.

Without seed treatments farmers would need to spray cereals an extra one or two times, use an extra 200 million litres of water and an additional one million litres of diesel to power their tractors and equipment:

Using Deter seed treatments for reducing slug grain hollowing in cereals potentially saves up to 1,600 tonnes p.a. of slug pellets being used in the UK.

Without seed treatments slug pellet use will increase:

In eleven UK sugar beet field trials assessing the impact of virus yellows, Poncho Beta shows an average 20% yield increase over untreated crops. Yield losses at this level experienced in the field would have a huge impact on sugar beet production.

In eleven UK sugar beet field trials assessing the impact of virus yellows, Poncho Beta shows an average 20% yield increase over untreated crops. Yield losses at this level experienced in the field would have a huge impact on sugar beet production.

Keep up-to-date with industry developments. Read a blog by Julian Little, Bayer Communications & Government Affairs, together with in-depth case studies. Discover how influential organisations are reacting to the EC proposals and follow links to media articles.

We would like to use optional cookies to better understand your use of this website in order to improve our website. Your consent also covers the transfer of your Personal Data in unsafe third countries, especially the U.S., involving the risk that public authorities may access your Personal Data for surveillance and other purposes without effective remedies. Detailed information about the use of strictly necessary cookies, which are essential to browse this website, and optional cookies, which you can reject or accept below, and how you can manage or withdraw your consent at any time can be found in our Privacy Statement