John Barrett, Director at Sentry which is a farming and rural advisory business who manage over 20,000 hectares across the country.

“There are different aspects to sustainability such as financial, environmental and rotation. The farm has to turn a profit first and foremost so it can provide the other aspects of sustainability.”

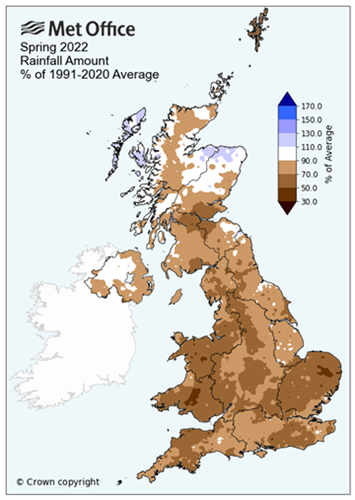

“Improving soil has been the starting point, twenty years ago Sentry began using more manures and organic materials on the soil. Organic matter content has risen, and soils are more resilient. For example, March saw up to 200% higher than average rainfall in many parts of the South and April to June 2022 saw up to 95% less rain than average. But the more resilient the soil the better it will cope with these extremes.

“In general, we see that crops are not as stressed and yields are more consistent, in addition healthy crops tend to be less vulnerable to pests, weeds and diseases. All of which helps improve environmental and financial sustainability.”

Where appropriate, Sentry managed farms have also reduced tillage which also contributes to soil health. Although, rotations with roots and farms without self-structuring soils can’t do this to the same extent. Each farm needs to be assessed and farmed according to it’s own soils.

According to Mr Barrett, cover crops are particularly important for retaining nutrients in the soil and preventing losses into water. Reducing nutrient levels in water is growing in importance and he expects many farmers will have more involvement with water companies in the future. It can be frightening to see financially what is actually leached out of our soils.

Sentry has carried out Cool Farm Tool benchmarking audits across all their farms as well as carbon audits, funded through the Food and Farm Resilience Fund, carried out by our own in-house consultancy business.

“The upshot of it, is that fertiliser is the main contributor to our carbon footprint, so our focus has been on optimising fertilisers - it is the ‘low hanging fruit’. Improving organic matter is part of this as it tends to increase nitrogen availability in the soil and help nitrogen use efficiency.”

“We use N testers to sample the crop and apply nitrogen accordingly. Last year, on a 110ha block of wheat in South Norfolk we manged to get 96% nitrogen use efficiency whereas, the benchmark used in carbon calculators is 60%. We are still learning but I know we can, and have to, get consistently better efficiency than 60%.”

The wheat yielded 10.23 tonnes from 165kg Nitrogen, the crop was destined for feed, however Mr Barrett admits that milling wheat is more challenging because of the protein specification but there are ways to do it without busting the carbon budget.

“There are quite a lot of tools available that added together will make the difference. We use an N tester, but perhaps an N sensor on the spreader could optimise rates a little more or we can use satellite imagery.”

Mr Barrett points out that setup and maintenance help to prevent overlaps and inconsistent spread. It will be hard to see with the naked eye but added together it means nitrogen application is not being optimised. We can’t afford financially or environmentally to have wastage.

“Timing is also important; the crop needs to be actively growing without heavy rainfall forecast that will potentially leach the nitrogen away. These are all fairly basic things, but you have to get them right if you want to optimise nitrogen usage.”

This season, like other farmers participating in Bayer’s carbon project, Sentry will look at the value of foliar N to replace the final 40kg split. As nitrogen prices have now dropped, the economic argument for foliar applications is not as strong but it can make a lot of difference to the carbon footprint of the crop.

Mr Barrett views carbon benchmarking as a way to future proof the business. Although carbon payments are relatively small at the moment, he expects demand for carbon will increase as all types of companies, as well as our own, will need to demonstrate how they mitigate carbon emissions. Likewise, schemes such as SFI are part of a bigger picture where farmers are paid for a range of services and products not just producing food.

This approach extends to rotation planning where he tries to avoid rigid thinking: “I’ve never been one for fixed rotations, you need flexibility to react to the market or weather conditions. Wheat is generally profitable and lower risk than some crops but there has to be diversity for a bunch of reasons – pests, diseases, black-grass, ryegrass etc. – so every crop, every season has to be judged on its merits. For example, one year we grew a lot of spring oats as the price was £240/t when beet was only £19/t, this has now flipped with beet up at £40/t improving the opportunity to turn a sensible profit.